|

| DeFord Bailey |

|

| The Harmonica Wizard |

But miracles of miracles, Bailey recovered; however, he suffered a couple of side effects. His growth was stunted, leaving him with a slight hunch in his back. He was short in stature, only 5 feet tall and walked with a limp. But that did not hinder Bailey’s future in music. Fortunately, he came from a musical family who played musical instruments. Lewis Bailey, his grandfather, was a champion fiddler. The music they listened back in the day was called “black hillbilly”. In addition to playing musical instruments, Bailey said all of his family could also sing and dance.

According to a PBS documentary, Bailey developed his playing style while confined to his bed. “He was confined to his bed for a year, and was only able to move his head and his arms. It was at this time that he started to develop his playing style. He would lie in bed and listen to the sounds of dogs howling, of wild geese flying overhead, of the wind blowing through cracks in the wall, and most importantly, of trains rumbling in the distance.”

Bailey’s aunt Barbara Lou gave him his first harmonica, then called mouth harp. He was a year old. He later said, “My folks didn’t give me no rattler, they gave me a harp, and I ain’t been without one since.” His biological father, John Henry Bailey, died in 1918, when his son was 19. This is when Bailey left rural Tennessee to join Barbara Lou, his father’s sister and her husband Clark Odum. Bailey’s mother died when he was just a tot, and his aunt became his foster mother. She and Odum worked for a prominent wealthy family in Tennessee. They convinced them to hire Bailey as a houseboy, performing menial chores around the mansion. Timing is everything in life, and while working for the Bradford family, Bailey’s musical talent was discovered.

“One day I was in the yard and she heard me playing. She said, 'I didn't know you could play like that. How long have you been playing?' I told her, 'all my life.' From then on she had me stand in the corner of the room and play my harp for her company. I'd wear a white coat, black leather tie, and white hat. I'd have a good shoeshine. That all suits me. That's my make-up. I never did no more good work. My work was playing the harp.”

Barbara Lou died in 1923, causing a family breakup. The PBS bio said Bailey took her death hard. Odum moved to Detroit, but Bailey stayed in Nashville working at several odd jobs. He was “rediscovered” while working as an elevator operator in the Hitchcock Building in downtown Nashville. One day a secretary with the National Life and Accident Insurance Company heard Bailey playing his harmonica. She was so impressed with him, she hired him to perform at a formal dinner at the company’s new building. That gig led to a bigger audience.

The year and date was October 5, 1925. A new broadcast station, WSM, went on the air. The PBS bio shows that the station, created by the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, was interested in presenting a first class image. It hired George D. Hay, one of America’s most popular announcers. Nicknamed Judge Hay, he had a fondness for folk music. He started a variety program called The National Barn Dance, while working at LWS in Chicago. Shortly after arriving in Nashville Hay started a similar program with a local champion fiddler named Jimmy Thompson. The show was a hit. On December 27, 1925, WSM and Judge Hay sent out a press release announcing that the station would begin playing an hour or two of old familiar tunes. The show’s name was The Barn Dance, later renamed the Grand Ole Opry.

During the fall of that year another station WDAD went on the air, a few months earlier than WSM. It was operated by a local radio supply store called Dads. Pop Exum, was the manager of the store and one of DeFord’s biggest fans. He made Bailey a regular on WDAD. According to PBS, “Pop had met DeFord at an auto accessory store that he had managed prior to Dad’s and where DeFord would come and buy parts for his bicycle. Another one of Dad’s regulars was Dr. Humphrey Bate, a country doctor who also played the harmonica. Dr. Bate’s band, later called the Possum Hunters, played for both WDAD and WSM. When Bate heard DeFord play he insisted that he join him on WSM’s new Saturday Night Barn Dance program.”

|

| DeFord Bailey in early years |

By 1928, Bailey had settled into a working routine with the Opry, appearing twice as often as any other performer. Because of Bailey the Opry attempted to attract a “colored” audience. “Opry and all other WSM shows were designed to sell National Life. A large portion of the National Life’s business consisted of small policies, popular with both white and black low income customers. Judged Hay told DeFord that half of National Life’s money comes from colored people and that DeFord had helped make those sales.”

i

Given that he was the most popular performer on the Grand Ole Opry, Bailey performed from 1927 to 1941. He was the only African American to perform on the Opry in its early history. Bailey toured with several of major white entertainers in country music. They performed at tent shows, county fairs and theaters across the country. Despite of his talent being equal to, or superior to White musicians, Bailey, in a segregated America, was not afforded the same accommodations when they went to restaurants. He could not use the White designated bathrooms or sleep in Whites only hotels. If Bailey was allowed to eat in a diner or restaurant he had to dine in the kitchen or stay in the car, where he sometimes slept if they could not find a safe boarding house for him in the Black community.

BlackHistory.com notes that “Bailey, with his musical talent, carried the (Opry) shows during the early years, offering a balance to other performers such as Uncle Dave Macon and the McGee Brothers. He had the soul of a jazz artist, often improvising on the spot, each of his performances were different and equally special. After a typically great performance of his classic train song, The Pan American Blues, Hay mouthed the phrase that would become music history: ‘For the past hour we have been listening to music largely from Grand Opera, but from now on we will present The Grand Ole Opry.

“Bailey’s popularity led the enthusiastic Hay to choose him as one of the Opry acts to be recorded by Columbia Records during a session in Atlanta, in early 1927. However, bad business practices made Bailey cancel this deal and sign with Vocalion Records. Vocalion, Brunswick's sister label, created a series. These series sessions yielded eight songs, including Pan American Blues, the only recordings by a Black performer in the entire series. A year later Hay set up the first recording session to ever take place in Nashville, luring the Victor label in town to record his Opry performers. Bailey took part in this historic session, cutting eight new songs in four-and-a-half hours. Three of these songs would later be released by Victor; the last song, John Henry, was released in 1932. Re-issue of the material were released as late as 1936.” The record label made money, but Bailey saw little of the royalties."

DeFord Bailey did not record any more songs after 1928, the same year a smaller radio station, WNOX, recruited him. But things did not work out for Bailey. He was not happy with the small salary he was earning, or the paternalistic treatment he endured at the station. He went back to Nashville in 1929, where he briefly reunited with the Opry. This time he negotiated a better income for himself. He met and married Ida Lee Jones several months later, and they had three children. This was doing to Great Depression and Bailey had to find more work to supplement his income. In 1930 he opened a BBQ business and shoe shine stand, in addition to renting out rooms in his house.

Several years later Judge Hay convinced Bailey to help publicize country music singer Roy Acuff’s Smoky Mountain Boys. He toured with them for a couple of years, helping catapult Acuff to stardom. However, when you read about Acuff’s rise in the country music and on the Opry, there is no mention of Bailey’s contribution. Acuff said on the PBS documentary: “I was an unknown and DeFord traveled with me for a long time. He helped me to get where I am.”

Photo to left: Fontanel co-owner Marc Oswald and director of hospitality Jamie Dudley. Fontanel Mansion is the new home of a rare, original 1978 recording of Country Music Hall of Fame DeFord Bailey's "Ice Water Blues/Davidson County Blues", along with the photos of Bailey with Grand Ole Opry cast members in the late 1920s.

In 1941 Bailey was working on his 16th year with the Opry. It was undergoing a facelift in an attempt to attract a more upscale audience. Bailey’s appearance on the show was short lived. A problem arose because the ASCAP required radio stations to pay fees for using its copyrighted music. ASCAP’s contract with WMS was up for a contract renewal in 1940, and ASCAP planned to double its fees. The station was not having it. Bailey was hard hit by the no deal. His music was copyrighted by ASCAP. So it amounted to no bigger fee, and no DeFord Bailey music.

Radio broadcasters organized their own company--Broadcast Music Incorporated--to copyright and catalog music specifically composed for radio. Edwin Craig, a stockholder in BMI, wanted performers on his show to write new songs, which would then be copyrighted by the newly formed corporation. The radio station boycotted. The PBS documentary stated, “Hurt, puzzled, and offended by the Opry's insistence that he now create new material, DeFord continued to perform his old tunes. By the end of July the boycott was over and NBC signed an agreement with ASCAP. Things returned to the way they were with one exception. After May 24, 1941, DeFord's name no longer appeared on the show's line-up. He had been let go.”

Judge Hay, in an unflattering evaluation of Bailey, wrote in a book titled A Story of the Grand Ole Opry, “That brings us to DeFord Bailey, a little crippled colored boy who was a bright feature on our show for almost 15 years. Like some members of his race and other races, DeFord was lazy. He knew a dozen numbers, which he played on the air and recorded for a major company. But he refused to learn any more, even though his reward was great. He was our mascot and is still loved by the entire company. We gave him a whole year’s notice to learn some more tunes, but he would not. When we were forced to give him his final notice, DeFord said without malice, ‘I knowed it was comin’ Judge. I knowed it was comin’.’”

BlackHistory.com writes: “It's a terrible thing for the company to say terrible things like that about me," Bailey said in an interview. "I can read between the lines. They saw the day coming when they'd have to pay me right, and they used the excuse about me playing the same old tunes. I told them for years, I got tired of blowing that same thing, but I had to go along with them, you know. They held me down . . . I wasn't free."

Bailey was also noted as saying, "I told’em I got tired of blowing that same thing, but I had to go along with 'em, you know. Gene Austin played on Saturday night when I was there. Played 'Blue Heaven' on his guitar. Well, I come back next week and had that down on my harp. They said,‘Naw, don't play that. That's their song. You play blues like you been playing."

Radio broadcasters organized their own company--Broadcast Music Incorporated--to copyright and catalog music specifically composed for radio. Edwin Craig, a stockholder in BMI, wanted performers on his show to write new songs, which would then be copyrighted by the newly formed corporation. The radio station boycotted. The PBS documentary stated, “Hurt, puzzled, and offended by the Opry's insistence that he now create new material, DeFord continued to perform his old tunes. By the end of July the boycott was over and NBC signed an agreement with ASCAP. Things returned to the way they were with one exception. After May 24, 1941, DeFord's name no longer appeared on the show's line-up. He had been let go.”

Judge Hay, in an unflattering evaluation of Bailey, wrote in a book titled A Story of the Grand Ole Opry, “That brings us to DeFord Bailey, a little crippled colored boy who was a bright feature on our show for almost 15 years. Like some members of his race and other races, DeFord was lazy. He knew a dozen numbers, which he played on the air and recorded for a major company. But he refused to learn any more, even though his reward was great. He was our mascot and is still loved by the entire company. We gave him a whole year’s notice to learn some more tunes, but he would not. When we were forced to give him his final notice, DeFord said without malice, ‘I knowed it was comin’ Judge. I knowed it was comin’.’”

BlackHistory.com writes: “It's a terrible thing for the company to say terrible things like that about me," Bailey said in an interview. "I can read between the lines. They saw the day coming when they'd have to pay me right, and they used the excuse about me playing the same old tunes. I told them for years, I got tired of blowing that same thing, but I had to go along with them, you know. They held me down . . . I wasn't free."

Bailey was also noted as saying, "I told’em I got tired of blowing that same thing, but I had to go along with 'em, you know. Gene Austin played on Saturday night when I was there. Played 'Blue Heaven' on his guitar. Well, I come back next week and had that down on my harp. They said,‘Naw, don't play that. That's their song. You play blues like you been playing."

|

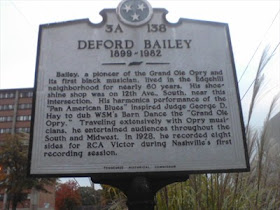

| DeFord Bailey Historical marker in Tennessee |

“Chicago harmonica player Joe Filisko offered the first musical bow to Bailey, playing the rousing and legendary Fox Chase, complete with the sounds of baying hounds and shouts of encouragement from the hunters. By the time the "chase" gained momentum, the crowd was already cheering. Also wielding a harmonica, DeFord Bailey Jr. showed his father's more sedate side by playing a slow and sonorous version of Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, one of the honoree's favorite hymns.

“Charlie McCoy, the harmonica wizard from the famed A-Team of Nashville session musicians, was up next with Bailey's Pan American Blues, an uncanny simulation of a train gaining speed and hurtling along the tracks. Finally, Carlos Bailey, DeFord's grandson, sang his own composition, The Legend of DeFord Bailey, backed by DeFord Jr. and the Medallion All-Stars. 'When DeFord died,' said the refrain, "a chorus of angels cried."

Thank you for sharing this information. I was doing some research on Charlie Pride, Darius Rucker and recently learned about DeFord Bailey. I appreciate your blog.

ReplyDelete